Below, you can review the Cady Family Justice Reform Initiative Principles as well as examples of how demonstration sites have implemented the them in their jurisdiction. The demonstration sites already had some practices in place that align with these Principles.

Problem solving approach

Principle 1 - Direct an approach that focuses on problem solving

The court must lead case management. In domestic relations cases, this requires directing a problem-solving approach.

Principle 2 - Involve and empower parties

Courts have ultimate responsibility for managing domestic relations cases but should empower both parties to play a proactive role in charting a course that is best suited to the family’s situation and needs.

Principle 3 - Courts are safety and trauma-responsive

Courts should be trauma-informed and trauma-responsive. Court processes should empower parties to make their own decisions and should be proactive in ensuring the safety of the parties, children, and others involved in the case.

Principle 4 - Provide information and assistance

Courts should provide clear, straightforward information to parties about the court process. Courts should provide assistance to self-represented parties including procedural information and available resources to assist the family.

Resolution 4’s first recommendation is “to ensure that family law matters receive the same level of prestige and respect as other court matters by providing them with appropriate recognition, training, funding, and strong leadership.” Frequent rotation of dockets or using family court assignments solely to train new judges sends a clear message that families are less valued by the justice system. The family court needs judges who exhibit strong leadership, advocate for ample training and resources, and lead improvement efforts.

Research demonstrates that strong and persistent leadership is essential to promote the type of court culture to do the difficult work of systems change. Judges are in a natural position of leadership, and they can leverage their position to champion change initially and build the internal leadership needed to establish and sustain new philosophies, processes, or practices. Effective strategies that judicial leaders can use to champion change include providing reasons for the changes in policies, establishing clear and frequent communication channels, and using available data to inform decisions.

Characteristics of court culture that contribute to a successful change effort include a commitment to serving court users and valuing their experiences; the capacity for honest self-evaluation and evolution; and a spirit of collaboration among court departments, court-related professionals, and community stakeholders. The Cady Family Justice Reform Initiative demonstration sites' adherence to these characteristics set the stage for their efforts.

One easily overlooked aspect of court culture is the importance of professionalism, training, and resource allocation in hearing family law cases. These cases require different expertise and access to resources than general civil or criminal cases. Lack of experienced jurists and resources to support families is a common lament in courts across the country, and this lack can cause real harm to families. In general jurisdictions, judicial officers oversee a variety of case types. In other jurisdictions, judges rotate between docket assignments, including family law cases. Diversity of jurisdiction and judicial rotation possess distinct advantages. Nevertheless, care must be taken to ensure that judges hearing family cases have the appropriate training and expertise in the diverse legal and non-legal issues that present in family cases.

Additionally, where domestic relations judges rotate quickly (every two years, for example), courts can be challenged to identify long-term champions. In some cases, courts can look to court administrators, commissioners and magistrates to drive improvement efforts. For example, Cuyahoga County’s efforts have been championed by Magistrate Serpil Ergun, a long-standing and nationally known jurist. For successful implementation of the Principles, court leaders must drive improvement efforts, acknowledging that the road may be long and that the court needs support from the larger community. Courts seeking a guidance for change management can look to the High Performance Court Framework , which has been applied to domestic relations.

Triage family case filings with mandatory pathway assignments

Principle 5 - Use a service-based pathway approach

Courts should establish a flexible pathway approach to triage domestic relations cases that matches parties and cases to resources and services.

Principle 6 - Streamlined Pathway

A Streamlined Pathway is appropriate for cases that require minimal court resources and little or no exercise of judicial discretion, and that benefit from swift resolution.

Principle 7 - Tailored Services Pathway

A Tailored Services Pathway is appropriate for cases that require more than the minimal resources of Streamlined Pathway cases but less than what are required for Judicial Specialized cases, and that presents an opportunity for problem solving between parties.

Principle 8 - Judicial/Specialized Pathway

A Judicial/Specialized Pathway is appropriate for cases that necessitate substantial court-based or community services and resources to reach resolution. This track is appropriate for cases in which parties cannot or should not problem solve together without court facilitation and supervision.

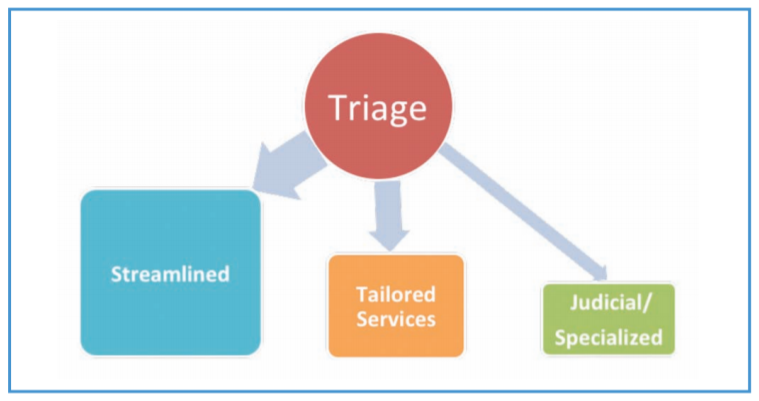

Principles 5-8 delineate a triage pathway approach that “matches parties and cases to resources and services.” CCJ/COSCA Resolution 4 goes even further, asking courts to “aggressively triage cases at the first opportunity.” Triaging a case at the first opportunity means screening a case at filing to determine case complexity, level of conflict, and services needed to resolve the case. This screening helps to determine the appropriate level and type of case management. The strong language of “aggressive” triage emphasizes the need for courts to assess case needs at the soonest possible moment. All courts, to varying degrees, engage in assessment to determine case management needs, but this assessment usually occurs several months into the life of the case. Rather than a court wide process for triaging cases, it is common for judicial officers to apply individualized criteria or processes that may not be clear to the parties. Approaching triage in a passive or non-standardized way can contribute to delay and lead to other negative case outcomes.

As set forth in an evaluation of Alaska’s triage and Early Resolution Program, “Courts can resolve 80% of their contested divorce and custody cases between self-represented parties in just one hearing with a special calendar that employs a problem-solving approach, triage, a simplified process, and early intervention.” With the assistance of volunteer attorneys, the court moves actively to identify the needs of the case and to clear them as appropriate, leaving the court better equipped to address new and backlogged filings. Families can save money and move forward with their lives more quickly.

Tailoring court response to the needs of a case leads to significant efficiencies, as demonstrated by Miami’s Civil Justice pilot. The Cady Family Justice Reform Initiative recommends aggressive triage and assigning cases to one of three Pathways: Streamlined, Tailored, and Judicial/Specialized. These pathways largely track those set forth in the Civil Justice Initiative and are also respond to the unique needs of family cases.

Many courts find it easiest to separate cases appropriate for a Streamlined Pathway from the rest of the caseload. Streamlined cases require minimal appearance and little or no exercise of judicial discretion, and include cases with limited issues, post-decree modifications of support or parenting-time, default proceedings and simple cases where the parties seek an order approving a stipulated agreement. Courts may differ in the case characteristics that they use to define the Streamlined Pathway. What is important here is to acknowledge that most parties come to court with partial or full agreement, and these cases should be identified at the earliest moment so that their cases can be processed expeditiously.

Often cases are screened and assigned to an expedited or Streamlined Pathway at initial case filing or first pleading; however, post-decree cases can also be appropriate. Case managers in Massachusetts, for example, screen post-decree cases at filing to identify cases appropriate for facilitated settlement conferences.

Each court differs in the factors they consider to assess eligibility for expedited processes. For example, Alaska considers length of marriage, length of separation, property or debt, age of children, existing arrangements regarding decision-making and/or parenting-time, history of domestic violence or current allegations, or whether location or relocation issues are pled. These objective factors allow for a brief screening process by court personnel who do not need to have advanced legal education.

There are examples in the Cady Family Justice Reform Initiative's demonstration sites of how parties can achieve finalization without needing to appear in court. Note that some state statutes require at least one appearance before a judge before finalization. For example, Ohio Revised Code 3105.64 requires that at least one hearing is held in all cases, where both parties must appear.

In Miami, a final divorce decree can be issued by mail without an appearance before a judge if both parties are in agreement, have no minor children between them, and have no substantial assets or debt to divide. In December 2018, Miami’s Self-Help Program implemented the opportunity for dissolutions of marriage with no children, property, or debt to be able to bypass a court appearance for a small fee. An initial piloting of this process led to 244 out of 300 eligible cases successfully avoiding the need for court appearance. The success of this streamlined strategy has pointed the way to expanded use of the criteria.

King County also has multiple processes in place to facilitate divorce agreements without a court appearance. When parties are in agreement from the beginning, they can schedule for their 91st day on the Final Decree Calendar. Any time after the initial filing, parties can schedule a final hearing in ex parte with 14 days’ notice. The Family Law Facilitators review these files in advance to ensure they are procedurally in compliance and prepare a detailed checklist. A Simple Divorce program is available to self-represented parties who agree on all issues and do not have children of the marriage and do not have significant assets (including income under $70,000 per year). If the parties work with the facilitators, Early Resolution Case Managers (ERCMs) will present agreed orders on the Status Conference Calendar without the parties needing to appear. Parties can fill out an application for the Simple Divorce, ERCMs will email final documents to the parties, parties sign and email back, and ERCMs present final orders on the Status Conference Calendar after 90 day waiting period.

The Pathways approach is adaptable to local legal frameworks and available resources. Courts define and shape their Pathways based on staffing levels, available services, and the individualized needs. One of the most common barriers to effective triage and case management is staffing, and in particular, the availability of qualified case managers to review documents, screen cases, identify case needs, and move cases forward. In the vision for the Cady Family Justice Reform Initiative, the court provides staff or automated tools that proactively guide litigants through each stage of the process and provide appropriate resources and assistance along the way. Case managers have one of the most significant roles in Family Court; however, the required skillsets and training vary widely because the role differs across courts.

What is the difference between triage and DCM (Differentiated Case Management)?

DCM and Triage both consider the amount of attention a case will need and establish a track that to help the case proceed to resolution. Some courts have had great success with this approach, as in Maryland. Maryland employs Differentiated Case Management (“DCM”) statewide and prioritizes the staffing of case manager positions across the state. Local plans establish processes according to local staffing. This is an example of a local DCM plan for Baltimore County.

Triage is a more aggressive form of case management, centered on the needs of individual parties and their cases. Cases are assessed through Case Management Teams. An ideal case management team is centered on case managers alongside staff attorneys and administrative personnel. The case management team engages the skills of staff to identify which pathways and services are most appropriate to meet the families’ needs at the soonest possible moment. Case management by staff permits judges to focus on decision-making. Typically, the responsibilities of the case manager include approving the cases’ assigned pathway, establishing an individualized case management plan, and communicating the plan with the parties and judicial officers. The case manager should also notify the assigned judge when a new case related to a family or an issue within an existing case arises.

The first demonstration site was the Family Division of the 11th Judicial Circuit of Florida (Miami-Dade County). The Family Division in Miami-Dade has already designed an innovative case management approach to support more efficient and effective case resolution. Their design uses pods of judges, magistrates, case managers, and court staff to provide a consistent team per case and connect cases to a judicial officer more quickly once the case is at issue. The Family Division consists of 14 Family Judges, 8 General Magistrates, 7 Family Case Managers, an in-house Mediation Unit, and a Family Court Services Unit.

The Civil Justice Initiative proposed a staffing model for civil case processing that relies on delegating responsibility of routine case management, like screening, to trained staff supported by technology. Case managers perform case processing functions across a tiers of case management responsibility based on the skills and legal expertise needed due to case complexity. The Cady Family Justice Reform Initiative supports this approach.

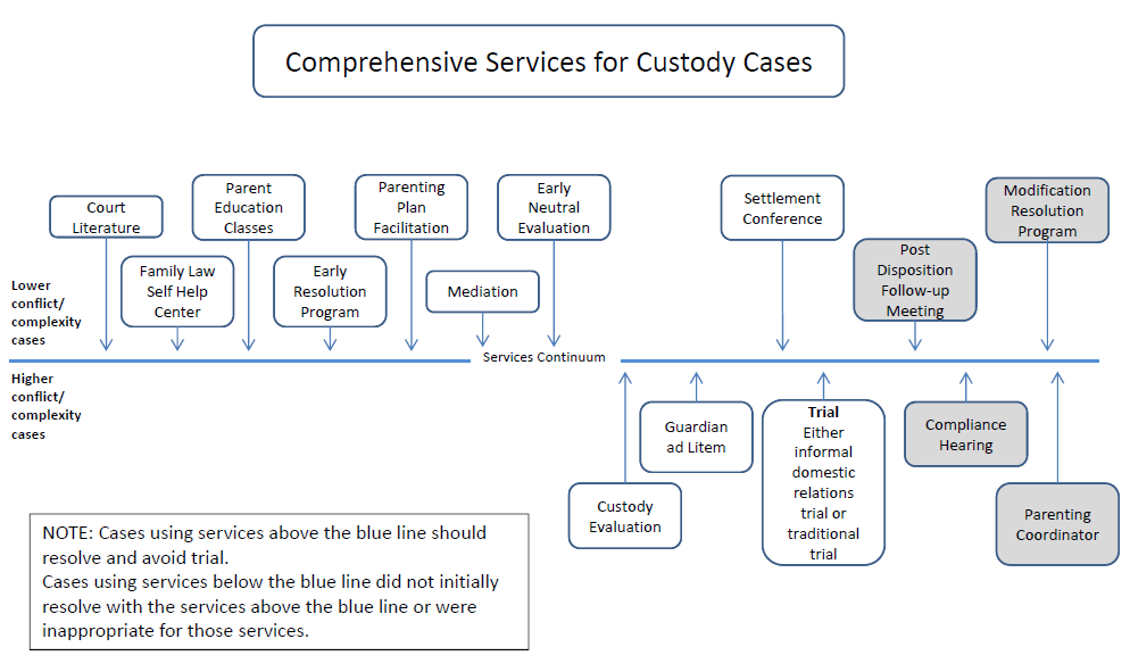

Cases that are not appropriate for the Streamlined Pathway require more support and assistance. Case managers must be well-versed in the services available both within the court and in the community to help parties come to an agreement, assess parenting skills, or receive support.

Alaska's Continuum of Services

Mediation and other non-adversarial, alternative dispute resolution processes are central to the Tailored Pathway. The Cady Family Justice Reform Initiative's demonstration sites offer options for parties to solve problems collaboratively. Some courts require alternative dispute resolution by statute or court rule, while others encourage non-adversarial strategy.

Pima County’s Conciliation Court provides parties with the ability to access Conciliation Counseling whether or not a divorce or separation case has been initiated. The Conciliation Court also provides free and fee-based services, such as mediation, parent education, and legal decision-making/parenting time evaluation.

In Cuyahoga, all parties, whether represented or not, are encouraged to resolve the case collaboratively. Court staff offers mediation for $250 per couple, with the charge assessed as a court cost and generally split equally between the parties. Parties may use private mediators if they wish.

In King County, alternative dispute resolution is required in all cases by local rule, unless waived, and there are several options of alternative dispute resolution available to parties. When both parties are unrepresented, Early Resolution Case Managers (ERCMs) can mediate at no cost, and Family Court Services social workers provide mediation on the parenting plan for a sliding scale fee. There are also mediation services available throughout the community.

Some cases require substantial court or community services to reach resolutions. These cases may include serious issues such as domestic violence or substance use. These cases often require greater judicial involvement, and case management responsibilities may be shared by both judges, case managers, and potentially other court staff.

For example, Miami Family Court Services offers a range of services to cases with high levels of conflict, including supervised visitation and counseling. There is currently a wait list for supervised visitation, indicating a high need for these services. There are community agencies that provide this service; however, the community agencies charge users while the Family Court Services can provide services at low or no cost.

The Landscape of Domestic Relations Cases in State Courts study found that a majority of cases (72%) involved at least one self-represented party. This figure is remarkably consistent with the civil landscape study conducted several years earlier, finding that in 76% of cases at least one party was self-represented. Because most state court civil and family parties are navigating a system designed for attorneys without an attorney, self-help is a critical court service. The Principles respond to this reality by putting forth an approach to domestic relations case management that assumes a heavy presence of self-represented parties. To provide access to justice for families, courts must approach this in two ways: simplify the processes so that non-lawyers can represent themselves effectively and provide assistance to parties so that they can meaningfully engage. CCJ/COSCA Resolution 4, In Support of a Call to Action to Redesign Justice Processes for Families, calls upon courts to “simplify court procedures so that self-represented parties know what to expect, understand how to navigate the process, can meaningfully engage in the justice system, and are treated fairly.”

One way that the Cady Family Justice Reform Initiative's demonstration sites support access to justice for self-represented parties is by providing information and forms both in-person at the courthouse as well as online. While many self-represented parties can access and are comfortable using online information and assistance, others may need “in-person” help for at least some stages of the process. Courts then must ensure that sufficient information is available online for those who need and want it, but also that parties can quickly reach self-help staff to take advantage of one-on-one options. The following examples from these demonstration sites illustrate how they support self-represented parties.

Cuyahoga County’s Help Center provides a variety of forms and written information, both online and at the physical location. The Help Center also offers one-on-one consultation with non-attorney staff members who are supervised by a lawyer director. The non-attorney staff receive training on how to deliver legal information instead of advice, court processes, and available resources and services, along with specific training on domestic violence and lethality assessment. The Help Center gathers user feedback via a short paper survey and uses this feedback to refine their operations.

King County’s Family Law Information Center (FLIC) is staffed by facilitators who are paralegals and serves parties on a walk-in or by-appointment basis. Written information on the court process and legal forms are available in-person and online, both on statewide and local court websites. Facilitators can provide information to self-represented parties, review completed forms, and help finalize cases by agreement. The website clearly delineates what family law facilitators can do as well as what they cannot do.

In addition to providing information and forms in-person and online, Miami-Dade’s Family Court Self-Help Program offers a free online chat and for-a-fee individual workshops to help self-represented parties complete required forms. The Self-Help Program has dedicated days in which only simplified cases (i.e., uncontested, no children, no property, etc.) are seen and resolved without the need for a court appearance.

Pima County offers self-help services in the Law Library, which was recently redesigned with the specific intention of serving self-represented parties. Librarians provide parties with books, self-service packets of forms, and brochures on legal aid and domestic violence services. The Law Library also provides access to a photocopier and computer-assisted legal research. There are free 30-minute legal clinics staffed by a volunteer attorney and a free settlement conference program with volunteer attorneys sitting as judges (pro tems).

Demonstration sites also prioritized simplifying processes, forms, and instructions for self-represented parties. For example, Cuyahoga is considering reducing the number of forms required to start a case. Similarly, Pima County is developing plain language forms from their existing versions, and King County is pilot testing online fillable forms.

This Pandemic Positives: Extending the Reach of Court and Legal Service report details how these courts, self-help centers, legal aid centers, and law/public libraries made the transition to remote services, including what their existing processes consisted of, how they messaged the changes to their customers, the ways in which they balanced remote services with in-person needs, the technologies they used, and the limitations caused by existing infrastructure.

As part of their involvement with the Cady Family Justice Reform Initiative, King County engaged in a simplification process where they developed a process map of their family law procedures and then identified duplication of efforts, inefficiencies, and opportunities to streamline the process. Simplifying processes not only maximizes efficiency and resources, but also improves parties’ abilities to navigate the court system.

Training and stakeholder partnerships

Principle 9 - Implement high-quality judicial and court staff training/education

Because of the complex, unique nature of domestic relations cases, judges and court staff must possess additional specialized knowledge, skills, and qualities.

Principle 10 - Identify and strengthen community partnerships

Courts managing domestic relations cases benefit from strong partnerships with community organizations, legal professionals, and service providers.

The complex and unique nature of family law calls for judicial officers and other court personnel to possess specialized knowledge, skills, and qualities. Not only must they understand family law, but they must also be fluent in the range of ancillary legal and non-legal issues such as bankruptcy, tax law, mental health and substance use disorders, child development, domestic violence, and other pertinent issues that may be present in family law cases. The issues may also change with societal change. For example, although each of the Cady Family Justice Reform Initiative's demonstration sites offer comprehensive training opportunities to family law judges, site representatives reported the need for more trainings, especially on how to identify human trafficking, and how to effectively manage joint domestic violence/family cases. Resources and opportunities to address these areas also shift over time, with new legislation, funding, and programming in flux as societal attention and demands change.

Courts should coordinate efforts to identify needs and provide regular training to judicial officers to ensure their competency in family law and ancillary issues. Note that commissioners and magistrates should receive the same level of training as judges. Of course, there are several professional organizations that offer training to family court judges, such as the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges, and many courts elect to develop their own curriculum. IAALS, the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System, listed the key training topics for those involved in family courts in The Modern Family Court Judge: Knowledge, Qualities, and Skills for Success. Equally important as the content of the curriculum is the design and delivery of trainings. Research on adult learning shows the value of highly interactive trainings with built in opportunities for application. Additionally, peer-to-peer interactions outside of a formal training, like professional mentoring programs, are beneficial to translate the material on the page into real world application.

The following examples describe some of the Cady Family Justice Reform Initiative demonstration sites’ processes for training new and existing judicial officers.

- King County’s experienced Family Court staff developed a comprehensive training curriculum for new judges. They deliver the curriculum yearly to accommodate their judicial rotation schedule; in their family court, rotations happen yearly, and judges sit for two years. This curriculum is supplemented with several additional training opportunities throughout the year.

- Cuyahoga County provides a two-week new judge orientation and requires 40 hours every two years of continuing education. The Supreme Court of Ohio’s Judicial College offers many courses each year, including content on domestic violence, emotional intelligence, autism spectrum, and parenting.

- Pima County offers several trainings throughout the year on legal and non-legal topics. A group of judges who attended a training on self-represented parties at the National Judicial College (NJC) is developing an in-house training for all judges, both new and seasoned, on how to manage cases involving self-represented parties.

Judicial officers are not the only court professionals who benefit from high-quality and comprehensive training. Case managers, self-help center staff, and other stakeholders also need to be informed on related legal and non-legal issues, including training on the triage model. Court staff may also require training in additional areas, such as customer service and legal communication. The guidance for Civil Case Management Teams from the Civil Justice Initiative is useful when considering the type of training required for case managers. As recommended in Principle 9.5, guidance on providing legal information versus legal advice is important, especially in settings where a law degree or legal/paralegal experience is not required for some public-facing positions. Leadership should provide clear explanations of what constitutes legal advice and give examples of appropriate communication with parties.

Data collection, evaluation and technology Innovation

Principle 11 - Improve ongoing data collection, analysis, and use of data to inform case management

Courts should gather baseline data to understand the landscape of their domestic relations caseload and then implement standardized, ongoing monitoring and development of evidence-informed practices.

Principle 12 - Collect and analyze user-evaluation metrics

Court and domestic relations caseload monitoring criteria should include user-centric metrics, such as party satisfaction, with various aspects of the process, including court resources and services. Courts also should consider periodically engaging former parties in exploring ways to improve the process.

Principle 13 - Implement innovative and appropriate technology

Courts should deploy innovative and appropriate technology solutions whenever possible to assist domestic relations parties, as well as judicial officers and court staff handling domestic relations cases.

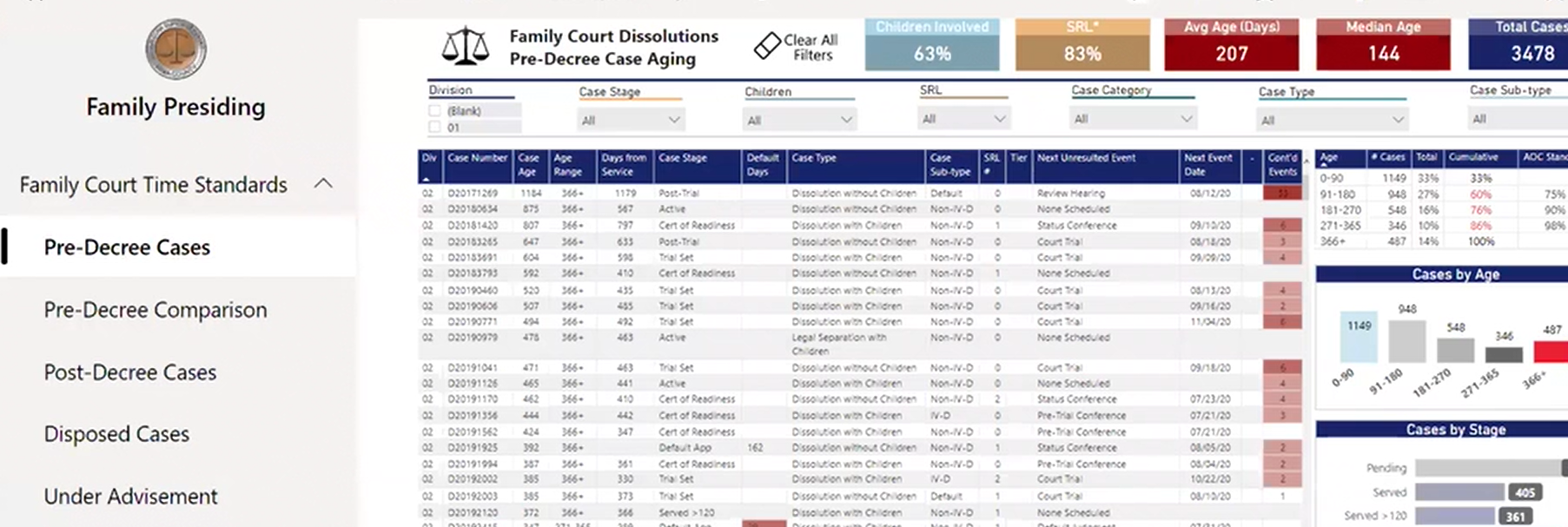

Family courts vary widely in their capacity to collect, analyze, and use data for case management purposes, and that diversity was visible across the Cady Family Justice Reform Initiative's demonstration sites. Some courts have departments dedicated to organizing case-level data so that court staff can use it to inform case management policy decisions; others have individuals who by training or talent have taken on the responsibility of bringing data to life through dashboards. Some courts make reports available for personnel to view, but do not formally discuss results. Others have routinized procedures for reviewing their data in meetings including judicial officers, court administrators, and other court personnel. Some courts rely on a limited set of performance measures focused on timeliness, while others have included measures of participant satisfaction and perceptions of fairness.

As Principle 11 notes, data can help courts understand their overall domestic relations caseload and monitor the impact of practice changes. Family cases necessitate performance measure that respond to the unique characteristics of these cases; see this resource for the Cady Family Justice Reform Initiative's performance measures. Often court data are organized around time standards, which represent critical case management benchmarks; however, family courts can also benefit from applying other performance measures, such as party satisfaction, perceptions of fairness, and family wellness post-decree.

Pima County, Arizona’s data dashboard pulls from the case management database so that the court can monitor Family Court cases nearing timeframes and ensure compliance with hearings, mediations, and parenting classes.

To realize well-being as a primary case outcome, courts need to know how a family experienced court and whether the court process satisfied their needs. Counting re-filings offers a minimal measure of how well a decree resolved a family’s issues but establishing a routine method of asking families about their court experience provides richer information. There are a variety of methods for gathering information directly from families and other court participants, discussed below.

| Comment Card | Kiosk | Survey | Focus Groups |

Control over sample | No control and typically low response rate, may over-emphasize extreme responses (positive or negative). Cannot generalize findings to entire caseload. | No control and response rate may depend on accessibility. Cannot generalize findings to entire caseload. | Different ways to select the sample, and response rate may depend on sampling strategy and survey length. If scientific sampling methods are used, can generalize findings to entire caseload. | Good deal of control over who is invited, but participation should be voluntary. Cannot generalize findings to entire caseload. |

Resources needed to collect data | Very easy to collect the data, but data entry can be time consuming. | After the initial expense of purchasing the kiosk, the data collection is low cost. | Low cost to collect the data, and if the survey is online, no data entry is required. | Typically requires a neutral party to facilitate the groups and a private space to conduct the discussion. It is possible to conduct focus groups via telephone or video. |

Amount of information collected | Typically includes very few items. | Typically includes one or two items. | Depends on the length of the survey, however, shorter surveys have higher response rates. | Ability to gather valuable contextual information that may not be detectable from surveys. |

Analysis | Requires resources to aggregate and analyze the data. | Typically automatic analysis. | If on paper, resources are required for data entry and analysis. Most online survey options include easy-to-use analysis tools. | Typically requires a neutral party to synthesize the data and identify themes. |

Examples |

Even courts with up-to-date data systems sometimes lack key details needed to understand trends in caseloads or to determine if current case management practices are effective. Important case characteristics related to complexity, such as number of children, amount of property, presence of complicating factors such as domestic violence or substance abuse, or number of events per case, may not be tracked in the court data system or may be tracked in a way that is difficult to aggregate. Additionally, valuable information about court services, like mediation and custody assessments, may be collected in a totally separate database making them difficult to obtain. The usefulness of this information calls for courts to work with service providers to develop data sharing processes.

Information on case characteristics not only helps a court understand their performance but can also be used at the beginning of cases to proactively determine how a case will be processed. The Principles support a flexible, triage approach that matches cases and parties and resources and services as described in the A Model Process for Family Justice Initiative Pathways. The Pathways approach suggests that information collected at the initial filing, such as number of children, degree of conflict, and finances and property, can be used to triage a case and assign it to the appropriate track: streamlined, tailored services, or judicial/specialized. If the case characteristics used to determine the appropriate pathway are captured in a data system, it is possible to automate the initial case pathway assignment. Automation not only streamlines the process, but also enables consideration of more sophisticated metrics, such as weighting certain clusters of factors or calculating expected rates of refiling, in pathway assignment. See examples for how automation has been used in the Civil Justice Initiative here.