An assessment of current and future needs establishes a foundation for the facility planning and design process. It determines the amount of space required and estimates the magnitude of need in the future. By focusing on current needs, and projecting needs into the future, a jurisdiction can commence a renovation or new construction process with a clear understanding of how immediate physical solutions and funding strategies fit into an overall plan for addressing long-term space needs. A good needs assessment study will minimize unpleasant future surprises.

The needs assessment may be done by the local government staff, or the advisory committee, and can be accomplished in three basic steps:

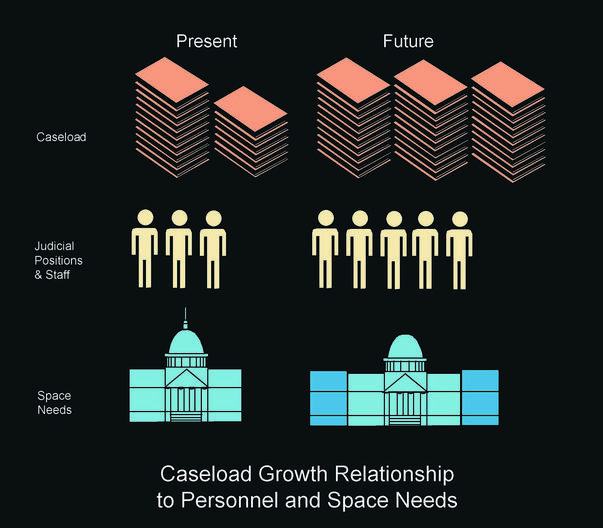

- Projecting future caseloads and workload.

- Estimating staffing and number of judges based on projected caseloads.

- Relating judges and staff to space needs, using established space standards.

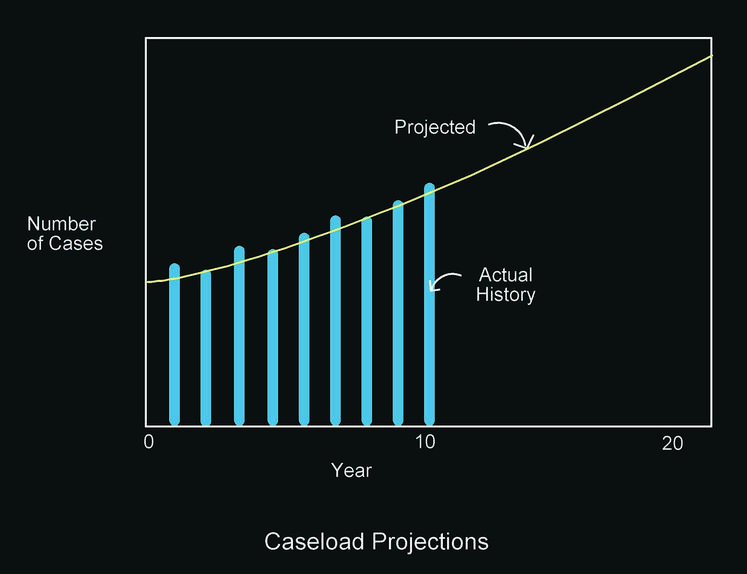

A good forecasting process extends 15 to 20 years into the future and should enable a jurisdiction to improve existing facilities, or to develop new ones, with some confidence in their longevity.

|

Projecting Future Caseloads

There are three principal forecasting techniques generally used in projecting court caseloads:

Qualitative

The best and most well known of the qualitative techniques is the Delphi method in which a group of practitioners (clerks, court administrators, judges, planners, etc.) participate in a focus group. All participants are shown the results of the first round of estimates and are offered the opportunity to change their initial estimates. The process continues until consensus is achieved.

Because nearly all available forecasting methods assume that the future will mirror the past, assumptions regarding future population levels, statutory and policy changes, and staffing levels should be clearly stated and discussed at the beginning of the project. Typically, forecasting with a combination of historical trend analysis, regression analysis, and factor analysis (such as population) will present the greatest opportunity for obtaining realistic projections.

Historical Caseload Trends

This method uses historical case filing data to construct a trend line. Past case filings are plotted and a trend is extended into the future, using such methods as exponential smoothing or moving averages. A basic assumption is that factors that have influenced caseloads in the past will continue to influence cases in the same manner in the future.

|

|

Historical Caseload Trends |

Independent Variables

This method examines the relationship between case filings and other variables, such as population, education levels, crime rates, per capita income, or unemployment rates to predict future caseloads. The use of other variables to predict future caseloads allows forecasters to relate case filings to some other measure which can also be projected.

The problem with most such variables is the difficulty in projecting factors such as per capita income or unemployment rates far enough into the future to be helpful. Because population is a variable for which viable future estimates are likely to exist in most communities, an analysis of population and case filings is usually the most reliable indicator.

Accounting for the Changing Nature of Litigation

One of the major complications in any type of forecasting is the changing nature of litigation. Court cases are not static; the law changes constantly. New types of cases are created by statute or case types may be consolidated, court cases have become more complex over the years, and sometimes cases (particularly criminal) may be counted differently. The introduction of technology is changing the way courts process and manage their caseload. All these and other factors increase and decrease the amount of work that it takes to process court cases which directly affects the number of judges and court staff needed.

- Milti-litigant Trials - Complex proceedings involve many attorneys and more courtroom participants, which then impacts courtroom space requirements.

- Discovery and Depositions - When attorneys spend more time on discovery and depositions, this lengthens the time to trial and increases the number of hearings.

- Malpractice and Civil Liability Cases - Increases in the number and complexity of malpractice and civil liability cases results in the greater use of expert witnesses. This requires courtrooms with larger evidence display areas, video-display terminals, video and teleconferencing capability, and evidence storage space to handle the technical nature of the testimony and number if exhibits.

- Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Programs - The use of mediation, arbitration, and other processes to resolve disputes outside the courts impacts courthouse design in several ways. First is in the reduction in the number of cases that proceed to trial will reduce the need for courtrooms and other formal dispute resolution venues. Secondly, if mediation is to be performed in the courthouse, additional informal hearing rooms will be needed in which to conduct such proceedings.

- Traffic Courts - Larger metropolitan areas are removing parking violations from the traffic or municipal court's jurisdiction and placing them under an administrative agency responsible for collecting fines. Only if someone wishes to contest the ticket is the case transferred to the court for trial.

- Demographics - As the population in many communities ages, the courts may experience an increase in cases relating to the elderly. In civil cases, the use of the courts to settle estates will increase; inter-generational conflict over the control of family assets may be resolved more frequently in the courts. Requests for the appointment of guardians ad litem may grow, along with cases of age discrimination, retirement disputes, and conflicts involving elderly persons. Specific legal problems associated with the young, such as automobile torts and violent criminal activity, may decline. The aging of our general population may be accompanied by complex legal questions surrounding life-sustaining technologies and right-to-die issues, the ethics of biotechnology and other medical advancements, such as organ transplants.

Reliability of Caseload Projections

Regardless of the method used, projections beyond 3-5 years can be very unreliable. Any long-term forecasting should be updated regularly in order to identify developing trends. As a general rule, the more observations, the better the reliability of the prediction. Twenty years is generally better than 10 years of data. The problem though when dealing with annual data is that the number and mix of cases 20 or 30 years ago may have little relevance to the the court of today. Many things may have changed from the complexity of cases, the types of cases being handled by the court, to the way in which cases are processed and resolved.

Throughout the forecasting effort, great care should be taken to ensure that historical definitions of case types are consistent. Ultimately, the thoroughness and judgment of the forecaster determines the efficacy of the forecasts. As staff projections will be used to define future space needs, and those needs will in turn generate budgets for capital improvements, it is important to emphasize the practical nature of the forecasting process.

Estimating Staffing Based on Projected Caseload

One method of estimating current and future judgeship needs is on the basis of dispositions per judge. Because of the varying amounts of time spent by judges on different case types, different ratios should be developed for each of the major case types, including civil, small claims, misdemeanors, felonies, delinquency, probate, and domestic relations. For further information on the various methods of determining judgeship needs, see Assessing the Need for Judges and Court Support Staff and Workload and Resource Assessments.

Because many non-judicial court positions are directly related to the number of judges, once the number of future judges is estimated it is possible to estimate the number of non-judicial personnel. For example, in many courts each judge is assigned a court clerk, secretary, law clerk, and bailiff. Depending upon the state, community, and level of court, the number and type of positions may vary. In this example, adding another judge will require four more non-judicial employees. In addition to these positions, other offices also are affected by changes in judicial staffing. The prosecutor and public defender typically will need additional attorneys to cover the new court.

Staff in the clerk's office not associated with judges may be projected on the same basis as judges by developing appropriate filings-to-staff ratios that would be applied to estimates of court filings.

Relating Staffing to Spaces in the Courthouse

In the early planning phases of a courthouse project, a rough estimate of the total building space is all that is required in order to develop some preliminary cost estimates and determine site requirements. At this phase, personnel headcounts are translated into space needs using rough ratios of square feet per staff person. For example, the ratio may be 300 square feet per person in a Clerk's office. This accounts not only for the personal office space but also all of the other spaces in the office such as public counter, workrooms, storage spaces, file storage areas, circulation, etc. Different offices may use a slightly different ratio. Ratios may be estimated by taking the current occupied square feet of the office and dividing by the number of persons in the office. Usually this will need to be adjusted to account for current overcrowding.

Judges, and the space associated with judges, can be estimated a little more directly. Usually, one judge equals one courtroom and one chambers. The spaces associated with each courtroom (attorney conference rooms, public waiting, jury deliberation, etc.) are easily defined. The total square feet needed per courtroom is calculated by using accepted space standards. The same is true for the chambers area. Once the square feet per courtroom and chambers are known, it is a matter of multiplying that number by the number of judges. To these two general categories of space are added some of the larger general building spaces such as an estimate for the lobby area, central holding, general conference or training rooms, etc.

To this total space it is necessary to then add a "grossing factor" to account for general building circulation, major building support spaces such as mechanical and electrical rooms, and the space taken up by stairwells, elevators, and external walls. The sum of these spaces is the estimated building gross feet.

In later phases of the project, a more detailed calculation of space is required as an early part of the design phase. This is referred to as the space program or the building program. The program is a schedule of every room and space that is to be included in the building, from the courtrooms to each janitorial closet, restroom, or workstation. The number of judges and staff is essential to this calculation, as well as the type and size of office each employee needs. Each space within each office, including staff break rooms, equipment closets, offices, open workstations, supply closets, counter space, copier stations, etc. must also be identified. To this we need to add a circulation factor and then a building grossing factor.

Next: Budgeting